Some time ago, I realized I know nothing about Paracho.

We all know the myths about its origin, but none of those stories truly satisfy our curiosity. Some say we are Tecos who moved from El Paracho over by Lake Chapala, others that Friar Francisco de Castro secured these lands for us by requesting them from Aranza, Ahuiran, Quinceo, and Pomacuarán. Still others claim it was the Santo Entierro (Holy Burial) that decided we should stay here after the Old Paracho burned down…

In short, we don’t know the truth. And I, not being an authority on history or a serious researcher, don’t presume to give you the definitive version. However, I’ll try to share what I’ve learned by questioning historians, musicians, researchers, and by reviewing various documents.

It starts with a doubt

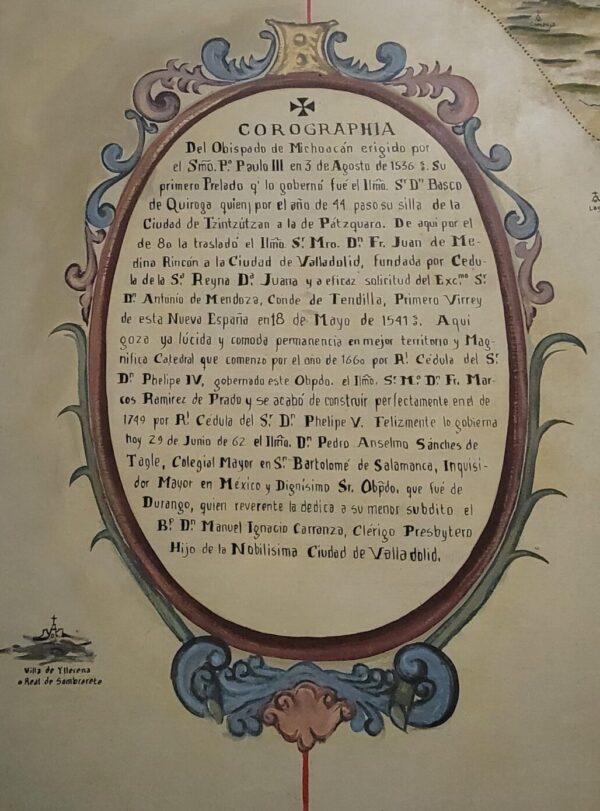

In 1860, a document was presented to the Mexican Society of Geography and Statistics by Dr. José Guadalupe Romero. This document compiled various data about the towns of Michoacán. The book, titled Noticias para formar la historia y la estadística del obispado de Michoacán (News to Form the History and Statistics of the Diocese of Michoacán), provides us with the following information about Paracho:

A town located in the Pátzcuaro highlands at 2° 45' longitude and 19° 29' 0'' latitude from the Mexico meridian. It already existed at the time of the conquest; its name in the Tarascan language means Old Clothes, according to some, or Offering, according to others, depending on the word from which it is derived. In the year 1534, the indigenous people of this region were baptized by Franciscan friars Fr. Martín de la Coruña and Fr. Francisco de Lisboa.

Sr. Dr. D. José Guadalupe Romero

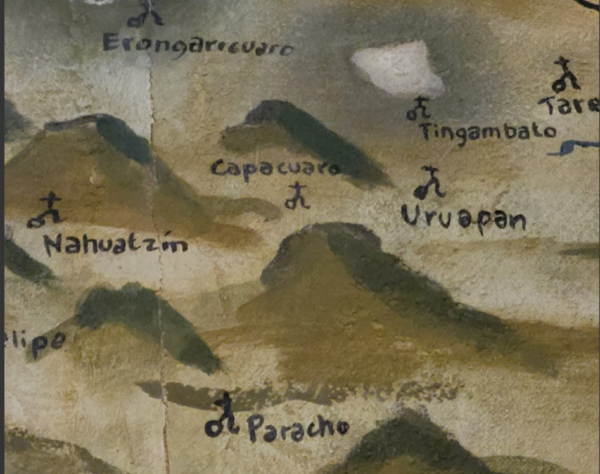

Paracho was already in its current location by the time the Spanish established the colony, which dismisses the idea that Paracho was formed due to Nuño de Guzmán driving the Tecos from their territory. Additionally, we can ascertain from some texts that the name “Paracho” appears to have a P’urhépecha/Tarascan origin.

19. Parácho, San Pedro, (ó Paráche, ropa bieja; (*) El B. D. Manuel de la Torre Lloreda, honor de este partido. aunque créo viene de Parándi, ofrenda),

Análisis Estadístico de la Provincia de Mechuacan 1822 Juan José de Lejarza

Paracho. Paratsi-o, lugar de mantas hechas a mano, de lengua tarasca: la final de lugar o, y la radical parahtsi, manta o pieza de vestido.

Nomenclatura Geográfica de México, 1897, Dr. Antonio Peñafiel

As for the term “Chichimeca,” I find no further evidence beyond what is repeated over and over, from Wikipedia to the official website of the Paracho City Council, where, unsurprisingly, no sources are cited for this information.

Walking backwards

So, how do we uncover the P’urhépecha origin of our town if we have always believed a different version?

In the Relación de Michoacán (1541), Chapter XXXI: How Hirípan, Tangánxoan, and Hiquíngare Conquered the Entire Province with the Islanders and How They Divided It Among Themselves and What They Ordered, it is mentioned:

And Hirípan, Tangánxoan, and Hiquíngare entered their council and said:

“Let us appoint lords and chiefs for the towns, as it will please the gods and bring peace to the people.”

And they went through all the towns and appointed chiefs.

The islanders took one part in the hot lands, and the Chichimecas another part on the right-hand side, in Xénguaro, Cherani, Cumachen; and thus, they pacified everyone. And a kingdom was formed. They also conquered Tacámbaro, Hurapan, Parochu, Charu, Hetóquaro, Curupu hucazio.

This account further supports the idea that Paracho was already established by the time the Spanish arrived, having been conquered at some point by Tangánxoan and later becoming part of the Tarascan kingdom.

As we move forward in the history of the town, we encounter blank periods, with little to no information for decades. So, let’s think: why do we still believe we don’t belong to this territory? Why do we still have that idea in our minds that we are not P’urhépecha?

There are many factors that have contributed over the years to this way of thinking among the people of Paracho. The very loss of identity has led us to neglect our communal ties and focus solely on individual benefits. It has made us feel detached from our own surroundings and, even worse, we have excluded ourselves from our culture.

A complicated path

There is something that is often heard in Paracho: the phrase “No one is a prophet in their own land.” It seems that here they take it so seriously that they push you to fulfill it.

There is a popular belief that foreign things are better. We see this in people who always seek American clothes, the luthiers who look for imported wood, those who prefer listening to Sinaloan music over Michoacan music, those who always seek English words instead of their regional equivalents. In short, the pop culture presented to us by cinema and television has swept away what once identified us as members of the P’urhépecha society. Women no longer wear naguas and rebozos as before, nor do men wear hats and sandals. In fact, it’s very likely that few people even know what the traditional attire in Paracho was, let alone ask for it to be used again. Our native language is no longer spoken, and even worse, there are many who deny their origins—those who proclaim that their birth certificate says they were born in Uruapan, Morelia, or Zamora, and despise their homeland.

So, it’s not surprising that we don’t know where we come from, and because of that, we can’t complain about not knowing where we are going.